You know when you’re reading Lord of the Rings, and you really wish the book would just let us spend some time with Rosie Cotton while she’s busy slinging ale at the Green Dragon?

Or is that just me?

Fans of science fiction and fantasy love good worldbuilding. But setting the stage by creating a magnificent new realm usually means the plot focuses on major historical arcs in said world. Once you’ve set up so much, developed all the minute detail, it makes sense to do the broad strokes and really create a mythology. How to Save the World; How to Win the War; How to Shape Reality With a Few Simple Building Blocks. They make great blockbuster film trilogies. They demand the creations of fan wikis and doorstopper guidebooks. They are the stories we take comfort in whenever the world seems a bit too claustrophobic.

Still, there’s something special about the stories that start small. That focus on the trials of individuals in the larger tapestry. That examine the everyday for people who may be extraordinary… but don’t quite see it in themselves.

Becky Chambers’s debut novel, The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, is precisely that sort of journey. There’s a big galaxy out there, but the Wayfarer is one ship with one crew—one tiny piece of a much larger picture. We get some history about the Galactic Commons that they’re a part of, filtered bits that we learn as we’re getting to know Ashby’s crew. We find out about what aliens humanity has made contact with, and what’s happened to planet Earth in all this time, where humans have migrated among the stars. We learn about Rosemary Harper, who begins her journey on this hodgepodge boat as a way of escaping her old life. We learn about Lovelace, the ship’s AI, and how people interact with technology so far in the future. There’s a big picture here… but we’re stuck in a very small corner of it.

And that’s precisely where we should be. The big universe-shaping anvils are out there, but that’s not what makes the story interesting or moving. Instead, it’s all about the cultural exchanges that we see among the crew, the odd little home that they’ve eked out in the middle of space. Rosemary is awed by their greenhouse, full of plants and open to the stars above. The crew sits down for family meals made by Dr Chef, who is always excited by the ability to switch up their dinners with new foods and herbs. One of the techs, Kizzy, has made Rosemary jellyfish curtains for her room to make the place more cozy. Jenks and the ship’s AI are in love, and Rosemary finds herself attracted to the ship’s pilot Sissix, who is a completely different species. There’s a wider plot and a greater context, but this is just a story about a crew in space going about their lives. And it is infinitely more engaging for that fact.

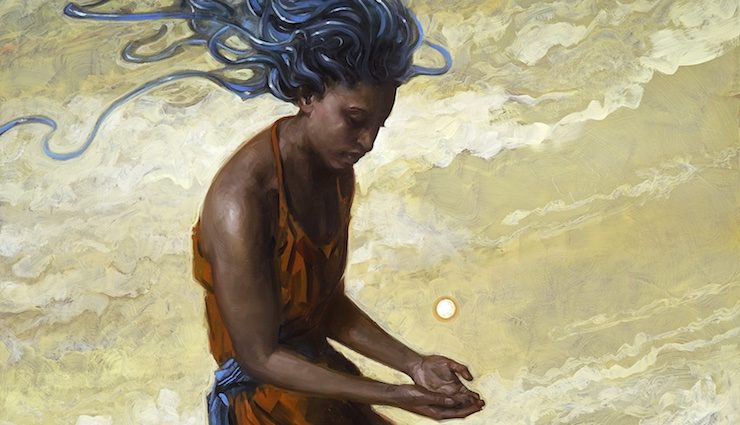

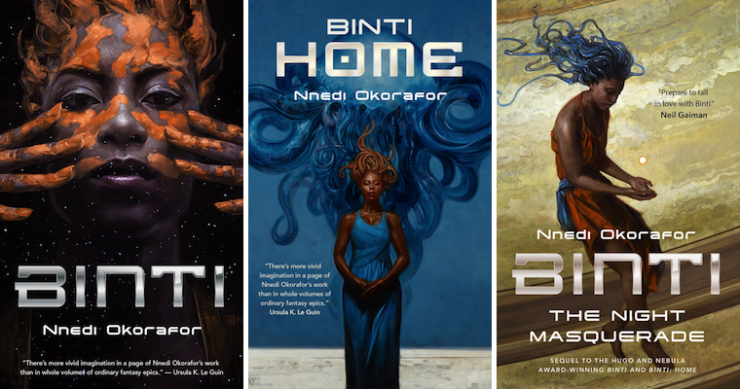

The Binti series by Nnedi Okorafor runs in this vein as well. On the one hand, Binti’s story is truly epic; what she goes through on her way to Oomza Uni when she runs head-on into the Meduse alien race is harrowing. These frightful experiences lead to a physical transformation, and Binti’s chance to broker a peace in a long-standing war between the Meduse and humans. In Home, she brings her Meduse friend Okwu home to meet her family and discover if she still has a place among her people. They react with extreme hostility at her abandonment, and her new choice in friends. In The Night Masquerade, Binti transforms once again, in a manner that she never expected. The story is writ large; the ways that Binti influences her universe’s political landscape is profound, and the multitude of changes that she goes through are sort we expect from heroes with a capital “H”.

Yet the pieces of Binti’s journey that are the most profound are all wrapped up in the little parts of her life that every human can find a point of connection to. Binti’s desire to leave the only home she’s ever known behind for a chance to attend university is the crux of the first story, and her reflections on what it means to make this choice are the heart of her journey. The clay she uses to coat her skin—revealed only later to have a greater significance—is a tenuous and much-needed reminder of where Binti comes from and all that she brings with her. And her desire to establish herself outside the common narrative told by her own people is ultimately a desire that most children find their way to as time moves on. Binti’s story may be epic, but the ways that she arrives in that story come from all those little human impulses and needs, not a magic prophecy told on her birthday by a wizard.

Though it may seem an odd departure of tone to be so similar, this is also one of the primary selling points for Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker Guide to the Galaxy. The Earth is destroyed to make a hyperspace bypass, and the reader is stuck hanging around with some English dude who couldn’t prevent his own house from being demolished. He then spends his time on one of the most powerful spaceships in the universe trying to instruct a computer on how to make the perfect cup of tea, and failing. Sure, we get an armful of Zaphod Beeblebrox, galactic president and charlatan, but even his escapades aren’t all that impressive. More importantly, nothing that happens on the Heart of Gold is of true import to practically anyone except the people traveling on it (and the people who are upset that Beeblebrox stole the ship in the first place).

You could argue that the desire to create larger stakes for the story is precisely where the film version of HGTTG falls down its duty. Arthur Dent’s travels are not interesting because he’s thrust onto a larger galactic stage where his importance is suddenly elevated. It’s precisely the opposite; Arthur Dent is fun to follow around because he’s such a stupendously boring person. Ford Prefect is an excellent galactic guide because he’s terrible at the job. We can see the larger galaxy all around us in Adams’s story, and he often goes out of his way to give us greater knowledge of the universe, but no one actually needs to read through the Hitchhiker’s Guide because that’s not an enjoyable exercise. What’s fun is watching Trillian, Ford, and Zaphod bring Arthur to a restaurant in the book’s sequel, where he tries his best to respond to an animal who cheerfully asks him to select which part of it he would like to eat.

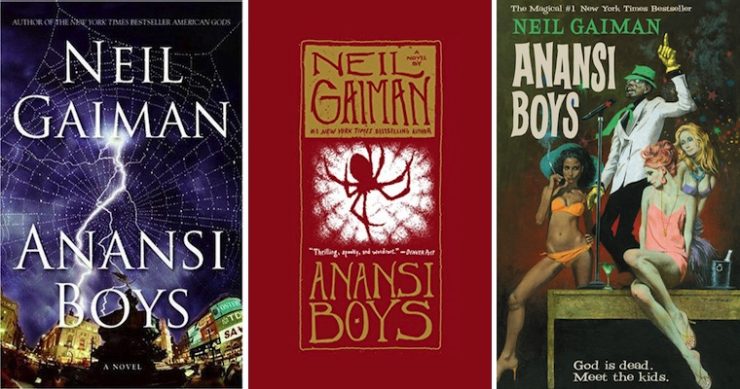

Though there are many facets to the American Gods universe that Neil Gaiman has created, its occasionally-overlooked spin-off, Anansi Boys, is an absolute delight. The larger universe of American Gods is an intricate thing that changes a whole universe of possibility, but the promise of that possibility is precisely what Anansi Boys delivers on—and in it, you find the incredibly normal son of a spider god having a rough time because his father’s death throws his life into chaos. Fat Charlie works a thankless job, has a perfectly normal fiancee, and learns from an old family friend that he has a brother who inherited all the special god-like powers in the family. When he makes the drunken mistake of letting a spider know that he’d like his brother to come for a visit, his very normal life is never the same again.

While Fat Charlie and brother Spider turning out to be the sons of an African god gives the story a somewhat grander scale, this is not a world-ending sort of yarn, and it doesn’t require the background of American Gods to make sense. It’s a story about the complexities of dealing with family, and figuring out how to define yourself alongside that familial history and heritage. Fat Charlie may not have the powers that Spider possesses, but he did inherit one very important ability from his father—the power to alter reality through song. His discovery of that ability gives him the chance to shape his own life in ways that he never thought possible, and get out from under the weight of a path that doesn’t really suit him.

While there’s nothing wrong with creating massive mythologies that power sprawling dimensions, these smaller tales fill in the corners and paint fictional worlds over with a personal touch that can render them more tangible than before. The chance to sit down at a table and share a meal, sing some karaoke, listen to some horrific poetry, these are the mechanisms that keep worlds turning when there’s no grand scheme to join in on. It’s not that I don’t want to read The Silmarillion… but I’d also love a comic about the life and times of Bill the Pony to round things out.

Emmet Asher-Perrin is gonna hold out for that Bill the Pony comic You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.